The wait for an autism diagnosis and subsequent intervention can be highly stressful for many families, especially when access to needed health and educational services also hinges on the approval of insurance and government agencies.

The wait for an autism diagnosis and subsequent intervention can be highly stressful for many families, especially when access to needed health and educational services also hinges on the approval of insurance and government agencies.

In a media release this year, the U.K.’s National Autistic Society announced that more than 150,000 children were awaiting assessment (1). Waiting lists are also relatively high in the United States (2). This can be attributed to factors such as a lack of healthcare professionals specializing in autism, challenges brought on by the COVID pandemic, and escalating rates of autism diagnosis (3). It may also be due to primary care physicians’ lack of knowledge or resources pertaining to autism.

Critical need for early action

The benefits of early intervention are profound and can greatly influence a child’s prognosis (4). A recent study, reported in the ARRI, indicated that children who received early intervention beginning at 18 months displayed enhanced communication abilities compared to those who started at 27 months (5). The impact of these critical early months cannot be overstated.

Parents taking charge

Aware of the pressing need, many parents choose to take charge of the initial assessment and begin therapy while waiting for professional guidance and support. For those navigating the wait, several valuable resources are available.

Screening for autism: Several reliable autism screening tools are available online, such as the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (MCHAT) on the Autism Speaks website (7), and ASDetect (8). These screening assessments can be useful in guiding and supporting parents and caregivers who seek professional guidance but should not be seen as a diagnosis of autism.

Intervention: There are numerous interventions available for autistic individuals, including various forms of Applied Behavioral Analysis (ABA), occupational therapy techniques, communication strategies, and more. Based on my 45 years of experience in the autism field, the common success factor across interventions is brain engagement as opposed to passive activities such as TV or repetitive computer games (9).

Early intervention and adapted ABA are proactive, parent-driven interventions that are especially useful for parents looking for immediate help (10, 11). The early phase of UCLA’s Young Autism Clinic stressed community engagement in providing basic ABA exercises and included relatives, friends, neighbors, siblings, and even acquaintances from church. Comprehensive teaching guides provide extensive instructions (12-14) and are available for online purchase at Amazon, eBay, and other booksellers. Having occasional expert consultants can also yield very positive results.

Approaches focusing specifically on language can be beneficial as well. For instance, one study that gained widespread attention from the autism community evaluated an intervention known as the “British Autism Study of Infant Siblings’ Video Interaction for Promoting Positive Parenting” or iBASIS-VIPPP. This technique focuses on helping parents understand their infant’s distinct communication signals and adjust their reactions in response to these signals.

The study involved 54 infants, ranging in age from nine to 14 months, who had siblings with autism and were therefore at high risk for developing autism themselves (15). Roughly half of these infants underwent 12 sessions of iBASIS-VIPPP, while the remainder did not receive any intervention. When evaluated at three years of age, the children in the intervention group displayed enhanced social communication abilities and a stronger sense of attachment security compared to those in the control group.

Another study focusing on the iBASIS-VIPPP approach was conducted in Australia (16). It included 50 infants between nine and 14 months of age, all of whom showed early signs of autism. Over a five-month period, these infants participated in 10 iBASIS-VIPPP sessions. Afterward, they were less likely to be diagnosed with autism by three years of age compared to 44 infants who received “usual care” in the control group.

Techniques providing vestibular stimulation, such as a platform swing, may also be beneficial (17, 18). Theoretically, these activities may activate parts of the brain such as the posterior cerebellum, linked to cognitive functions including language processing (19). It is important to consult with an occupational therapist for proper guidance, especially if your child has seizures.

To promote social interaction, I often encourage parents to facilitate connections with children in their neighborhood (20). Typically, peers slightly older or younger are more receptive. Incentives, even if nominal, can nurture friendships.

In an ideal world, no child should face delays in receiving essential services. However, financial constraints and staffing shortages pose a challenge, and a remedy appears elusive at this point in time. If you are one of the many parents waiting for a diagnosis and professional intervention, I hope the approaches I have discussed here will help you turn frustrating wait time into valuable teaching time.

Stephen M. Edelson, Ph.D.

Executive Director, Autism Research Institute

References are available at www.ARRIReferences.org

This editorial originally appeared in Autism Research Review International, Vol. 37, No. 4, 2023

ARI’s Latest Accomplishments

Connecting investigators, professionals, parents, and autistic people worldwide is essential for effective advocacy. Throughout 2023, we continued our work offering focus on education while funding and support research on genetics, neurology, co-occurring medical

Biomarkers start telling us a story: Autism pathophysiology revisited

Learn about emerging research on biomarkers and autism from a recent ARI Research Grant recipient. This is a joint presentation with the World Autism Organisation. The presentation by Dr.

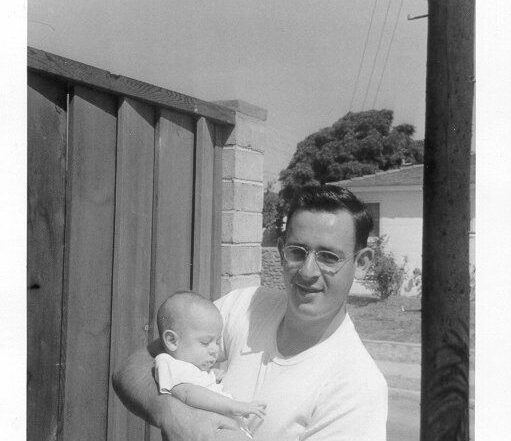

Editorial – Bernard Rimland’s Impact: Sixty Years Since the Publication of ‘Infantile Autism’

In this milestone year of 2024, the Autism Research Institute commemorates the 60th anniversary of Dr. Bernard Rimland’s groundbreaking work, Infantile Autism: The Syndrome and Its Implications for a Neural Theory of